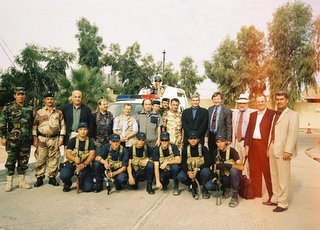

NCF Delegation in Iraq

Heading out for the Ninevah Plains (North of Mosul)

NCF Trustee Ambassador Mark Hamley

Smiling for the Kalashnekovs

Smiling for the Kalashnekovs

The NCF would like to invite comments or questions on the following report on our work in Iraq.

STATEMENT FROM

THE NEXT CENTURY FOUNDATION:

INTERNATIONAL OBSERVERS OF THE

REFERENDUM FOR IRAQ’S CONSTITUTION

As the only international observers operating at large in the interior of Iraq and accredited as election monitors to the Independent Electoral Commission for Iraq (IECI)[1], we issue the following comments on the October 15 referendum on Iraq's constitution.

Overall, we judge the referendum to have been honest and the result to accurately reflect the views of the Iraqi people. Regardless of this credible effort, there were concerns in some of the districts we monitored.

Allegations with regard to intimidation, inadequate numbers of voting centres, and other irregularities were received. Nevertheless, it is our strong impression that the election proceeded in a fair and, in most instances, unimpeded manner.

Preparations for the vote in both rural and urban areas appeared to us to be extraordinarily good, with active committees meeting on a daily basis in the days before the vote to make arrangements, liaise with governorate electoral centres, and to iron out security and other logistical issues.

Our report addresses most of the allegations received, some of which were substantiated and which include instances of intimidation, denial of access to the vote, inadequate numbers of polling centres, and inaccurate electoral lists.

These grievances notwithstanding, we issue this statement to make it clear that none of the above issues, though each is of very great concern, was of sufficient scope or seriousness, to impact substantively upon the final result, either at the governorate or national level.

THE NEXT CENTURY FOUNDATION:

INTERNATIONAL OBSERVERS OF THE

REFERENDUM FOR IRAQ’S CONSTITUTION

As the only international observers operating at large in the interior of Iraq and accredited as election monitors to the Independent Electoral Commission for Iraq (IECI)[1], we issue the following comments on the October 15 referendum on Iraq's constitution.

Overall, we judge the referendum to have been honest and the result to accurately reflect the views of the Iraqi people. Regardless of this credible effort, there were concerns in some of the districts we monitored.

Allegations with regard to intimidation, inadequate numbers of voting centres, and other irregularities were received. Nevertheless, it is our strong impression that the election proceeded in a fair and, in most instances, unimpeded manner.

Preparations for the vote in both rural and urban areas appeared to us to be extraordinarily good, with active committees meeting on a daily basis in the days before the vote to make arrangements, liaise with governorate electoral centres, and to iron out security and other logistical issues.

Our report addresses most of the allegations received, some of which were substantiated and which include instances of intimidation, denial of access to the vote, inadequate numbers of polling centres, and inaccurate electoral lists.

These grievances notwithstanding, we issue this statement to make it clear that none of the above issues, though each is of very great concern, was of sufficient scope or seriousness, to impact substantively upon the final result, either at the governorate or national level.

Availability of the Document

Some elements of the population, particularly from minority groups such as the Christians, were bewildered by the bombardment of media comment about the importance of this referendum in view of the absence of copies of the constitution in written form, which had been promised but which were unavailable in many regions. In major urban centres, like Kirkuk and Baghdad, this was not a problem, and copies of the constitution were eventually available, albeit only two or three days before the referendum. They were never available in adequate numbers (or in adequate time) in many other instances. This problem was aggravated by reports that the constitution was still being amended up to the date of the referendum, and that the population was expected to vote on something they had not seen.

Dohuk Governorate - In Akra town, there was only one copy of the constitution available prior to the referendum. No where, within the Dohuk province, was there more than a token number of copies distributed by October 15.

Suleimaniyeh Governorate – In Halabjah, 200 copies went to officials but not a single copy went to the people.

Ninevah (Mosul) Governorate –In the Nineveh plain, no copies were received by substantial minority groups, such as the Yezidis and the Christians.

False statements from United Nations officials in Baghdad that copies of the constitution were available throughout Iraq served to reduce the credibility of an otherwise excellent effort on the part of the UN this time around.

Pre-Marked Ballot Papers

There were notable allegations, some substantiated, of ballot stuffing or pre-marked ballot papers having been given to poorer people in last January’s elections, in cities such as Baghdad and Arbil.

We noted no such practices during this referendum. However, in any general election, increased vigilance in this regard will be warranted, given the increased stakes for individual participants and their political parties.

We would also wish to encourage further diligence at polling stations in the ethnically explosive city of Kirkuk. Here, ethnic tensions are at high level. One credible election observer, with whom we are associated, informed us during our visit to the city that sometimes tellers at polling stations might get tired or wish to take comfort breaks at which point observers from the various political parties would “step in” in an effort to be helpful, taking the place of the tellers. This is not good practice and should be discouraged in the future.

The IECI

The conduct of this referendum by the Independent Electoral Commission for Iraq (IECI) was splendid. This was an efficient exercise, and they are to be commended. Given the prevailing security environment, it is remarkable that they achieved such a good turnout with relatively modest amounts of controversy.

However, we did discern a number of criticisms directed at the IECI with regard to follow-up on the January 2005 elections. Complaints filed by observers, political parties, and concerned citizens were not always handled efficiently and, in many instances, no response at all was received. Staffing levels at the IECI should be increased to enable better transparency and feedback.

Also, registration for observers was arduous to say the least. Indeed, one of our own election officials found it difficult to enter the Green Zone to register our organisation. Whatever the reasons for this, it would help if a second accreditation unit were set up well outside the Green Zone, perhaps at one of the well-fortified hotels such as the Palestine or Sheraton (the spate of car bombings directed at these two sites on October 24 notwithstanding).

We would single out local IECI offices in Dohuk and Kirkuk for particular commendation for the diligence and efficiency with which they carried out their tasks, both before and during the October 15 referendum.

We were concerned about the degree to which the local IECI office in Mosul (Nineveh Governorate) appeared unable or unwilling to serve the people of the minority groups in Nineveh Governorate. To avoid a recurrence of problems noted in both the January legislative elections and, to a lesser degree, during the October 15 referendum, we would urge consideration of the establishment of a second IECI office to serve towns and villages in the Nineveh plain to operate independently of the Mosul IECI.

It is our intention to provide additional monitoring in Southern Iraq during the forthcoming December elections where many allegations remain unanswered from January. A general election is different from a referendum of this nature and is likely to involve increased interference from the various political parties involved. In order to respond adequately to this challenge, the IECI will require additional staffing and support from both concerned Iraqis and the international community.

Areas denied the Vote

Although a number of towns and villages were denied any access to the vote in January -- particularly towns with minority ethnic communities -- this problem was not a major factor in the October 15 referendum. Towns denied the vote previously, such as Al Kosh (Christian) and Bashika (Yezidi) (both of which are located on the Nineveh plain), were given the vote this time around.

Security

As a general rule, security was a key consideration on voting day. This was particularly so in cities like Mosul with its “three rings of security” policy. This meant that residents had to undergo an initial check, a metal-detector check, and a final pat-down check. All of this, under normal circumstances, would be excessive. However, given current security constraints, there is little alternative.

In other areas of Iraq, security was less diligent but adequate. In general, levels of security were high in towns but almost non-existent in villages.

Polling station availability

In general, this was more of a problem in rural areas, rather than in the towns. Most towns were well-served, if not over-served, with numbers of polling stations in some instances only two blocks apart. In rural areas, where a fuel shortage added additional logistical problems, the lack of adequate polling station provision was critical to securing maximum voter turnout. The IECI made excuses such as “the polling station availability is determined by the computer programme,” but such excuses sound as lame as they actually are.

In practice, there was gross disparity. Cities like Arbil had so many polling stations as to appear almost over-served, whereas small towns where minority communities were dominant were sometimes grossly under-served.

The worst instance of this that we noted was the Yezidi town of Bashiqa in the Nineveh Plane. Here, where upwards of 14 polling stations were required for Bashiqa and its extensive voting district, only five were initially provided. Following complaints from the community and our own interventions, the number of polling stations was increased from five to a total of six, but this number was still grossly inadequate. Sixteen would have been preferable. Bashiqa has 40,000 registered voters, of whom 25,000 (61%) voted. Had a greater number of polling stations been available, undoubtedly the turnout would have been far higher.

In view of the considerable pressure exerted on the Mosul IECI to increase the number of polling stations for this Yezidi community which had been denied the vote entirely in the January elections, and in view of the failure of relevant Mosul officials to respond in a forthright manner, we can only conclude that the absence of action was condoned for prejudicial reasons. This might have been because the minority community involved was composed principally of Yezidis. Or it might have been condoned because this region is strongly supportive of the Kurdish Regional Government and would have voted against Sunni positions popular in Mosul itself.

Whatever the reasons, steps must be taken to ensure that this situation is rectified in time for the December 15 general balloting. Unfortunately, Mosul electoral officials have not been good at their word in the past. We were given assurances prior to the referendum that adequate polling stations would be provided. We do not believe that the addition of one polling station was adequate and will be looking for a significant redress of the situation by December.

We would stress that the number of polling stations available has a severe impact. Arbil province, with on average one polling station per 3,000 voters had the highest turnout in Iraq at 96.93% of the electorate. Ninevah province, with its poor polling station availability, had a turnout of a mere 54.84%. Obviously security was a factor but poor polling station availability is a critical issue.

Note: The Yezidi are a substantial religious minority who pray towards the sun and consider angels as worthy of the highest respect. They are particularly common in Northern Iraq. In the Yezidi town of Bashiqa 92% of these whom voted “yes”.

Further note: for logistical reasons, we were unable to check the towns of Singar and Talkeif, both of which were also denied full participation in the vote in January. We intend to monitor the situation in both towns carefully in December.

Fuel

In many rural constituencies, inadequate fuel supplies hampered the ability of people to get around both before and during the referendum. Acra town in Dohuk Province is a case in point. Here an able electoral committee did outstanding work. However, in a country with no postal vote and with an extensive rural constituency, fuel shortages (which are severe in some areas) meant that the elderly and the infirm, who needed to be taken to a polling centre some miles distant to vote, were effectively disenfranchised. In Acra, fuel shortages were so severe that they even impacted on the ability of the police to get about to deliver and retrieve ballot boxes.

Indeed it is not only the elderly and infirm that are disenfranchised by the fuel shortages. They also create problems for the poor.

We noted when crossing the border from Turkey more than one week prior to the vote, that 3971 trucks were held up at the Turkish border crossing, of which 926 were fuel tankers. Also during two days prior to the election, whilst the border on the Iraqi side was closed,[2] another 4000 trucks were held up at the border, with more than 1000 additional fuel tankers included in this number.

Intimidation

There was remarkably little intimidation in this election, given the nature of the present situation in Iraq.

There were allegations, which we have been unable to substantiate, that Turkoman voters in Kirkuk were intimidated by some parties to vote ‘No’.

There are substantiated allegations of intimidation in Baghdad in an attempt to stop voting altogether. Some of our own election monitors had been intimidated.

There was intimidation of Arab spokespersons in Kirkuk in a quasi-successful attempt to stop free speech. One blatant example of this took place in our presence. Sadly, levels of hatred and prejudice in Kirkuk (a city with marked ethnic and religious divisions) are extreme, as the direct result of Saddam’s forced displacement of over 300,000 of the area’s inhabitants (the bulk of whom were Kurds) and their substitution by equal numbers of Sunni and Shi’a Arabs from other parts of Iraq.

We were particularly disappointed by the intimidation of voters in Al Kosh. Here a. security officer attempted to enter the polling station, intimidated local voters throughout the day, and attempted to enter the count with a group of thugs. The local police stood their ground and deserve particular commendation, evicting the security officer from the polling station. The turn out was good, and 16,703 of Al Kosh’s 21,800 registered voters cast their ballot in the referendum. In the end, the vote was fairly counted without manipulation.

Bad practice at polling stations

A complaint verified by ourselves and received from voters in Kirkuk, in regard to bad practice, was the use of election posters within polling stations. Thus, in this instance, polling station posters showed a voter casting a “Yes” vote. Clearly this action does not contribute to the unbiased environment required in a polling station and creates a bad precedent for the forthcoming general election in December.

Manipulation of the national count

This would be difficult, if not impossible, in view of the fact that polling stations each count their own vote and make three copies of the voting form. One they keep. One they forward to the provincial IECI office. One they forward to Baghdad.

Concerns have been expressed that there is no continuously observable process, because the announcement of the result in the Green Zone is a distinct event, separate from the count itself. This does make the process appear less transparent. The situation will be adequately rectified when the full results for every polling station and the calculations showing the summation of these into the total vote for each governorate respectively are made available for inspection. We have been assured by the electoral adviser from the United Nations Assistance Mission to Iraq that these details will be available on request within a reasonable time-frame. We intend to check these results for the controversial Ninevah governorate. We have every reason to believe we will be able to do this. If this does not happen to our satisfaction we will make the matter public before the forthcoming December elections.

The Next Century Foundation recruited its own team of monitors to attend the Baghdad count and many of the members of this team participated in the monitoring of the former elections back in January 2005. They reported that, “there is a very big difference in the whole process” this time around. They found the procedures adopted more credible and more transparent. This assessment was not unique to our own monitors. Other organizations also reported a dramatic improvement in levels of transparency at this referendum as compared to the January elections.[3]

Observers

There were no foreign observers in any of the regions we visited other than ourselves. There were foreign observers in the Green Zone (and possibly in greater Baghdad / Basrah), and these observers we understand were to have recruited local teams. Though we came across no such local teams recruited by international organisations in the regions we visited, we are aware that, in all, the IECI registered 15 International Observer Groups that accredited almost 700 observers.

We received a complaint from our own observers that all electoral monitors were removed from the count in the green zone on 20th October, whilst the counting was still proceeding. We are assured that this was the result of a misunderstanding and have every reason to believe that this unacceptable practice will not be repeated.

In general, independent Iraqi observers were absent from most polling stations in larger urban areas, although they appeared more likely to be present at polling stations in the smaller towns. The best independent observers we noted were often local lawyers who seemed to regard it as their civic duty to take on this work. They were noted in practically every polling district we visited. Indeed, virtually all independent observers visible during our visits in the interior of Iraq were lawyers. In all, the IECI accredited 53,000 independent observers for the constitutional referendum.

In big towns and cities, there tended to be more observers from political parties. IECI accredited over 120,000 political agents for the constitutional referendum. Many of these representatives were found seated as observers right alongside the ballot box. Though these seemed to be people of good will with little desire to influence the vote, we would recommend that, in the future, observers from political parties be kept out of the actual room in which the ballot is cast. Observers from the political parties can and should be invited to the count, however, but only where there is no chance that they may intimidate those who are actually tallying the ballots.

Inadequate voting lists

This was a problem in small towns, most particularly in Suleimaniyeh region. In the January election, Halabja town suffered in this way. In the October 15th referendum, there were problems in much of the wider region. Dhukhan town was a case in point with many names missing from the voting lists that had been registered in January. Upwards of ten per cent of the electorate in this region was disenfranchised in this way, according to local election officials. This failure, whether deliberate or accidental, caused considerable local distress. The senior electoral officer for Dukhan stated that previously (in January) voting lists had arrived early giving them time to check and correct the lists. But not this time. The people blame Baghdad for this failure, adding yet another complaint against the central government.

Dohuk also had some difficulties of this kind, though to lesser degree.

The Local Count

We were disturbed to note that the local count was almost always conducted at the polling station. There are dangers in this. We do not suggest that the count be conducted nationally in Baghdad, but we wonder whether the count might better be conducted at regional level to reduce the opportunity or inclination for fraud.

Conclusion

The Next Century Foundation welcomes correspondence on any issues or concerns from the people of Iraq. We intend to monitor the December 15th elections and will take up issues raised with us prior to that date. Comments to NCFIraq@aol.com

Overall, we regard this referendum as having been fair -- despite minor local irregularities. Though these were regrettable, they had no significant effect on the final outcome.

Signatories to this report are :

Mr. William Morris, Secretary General, Next Century Foundation

Hon. Mark Hambley, Trustee, Next Century Foundation

Date: 25th October 2005

[1] Numerous international observers were present, but the general practice was to employ local Iraqi observers on their behalf (which is entirely credible) whereas we travelled the interior ourselves.

[2] Closed by Iraq in this particular instance, not by Turkey, for reasons of security during the election period.

[3] For instance the Tammuz Organization for Social Development (TOSD) reports that, “the counting process . . . is characterized by preciseness, technically it is much better than the process that took place in the previous elections.” 21 October 2005, E-mail: tammuzftsd@yahoo.com

2 comments:

We have applied for the breakdown of the Ninevah and Mosul votes from the IECI but have yet to get it.

Hello William n Veronica n everyone at NCF. Greetings from Auroville, India. I attended a carol singing gathering here on the 21st n my thoughts were with you. I scrolled the blogger n it looks inviting. I'm at an internet cafe so my curiosity will have to wait till I get back to London. Love to all, Elizabeth

Post a Comment